The Grape Man of Texas

Benjamin Franklin, Nikola Tesla, Alexander Graham Bell, Katherine Johnson and Diane Fossey are all well-known American scientists credited for their inventions or discoveries. You, of course, know about Thomas Volney Munson. If you do not, you should, because his research in viticulture saved modern viticulture from extinction.

American horticulturist Thomas Volney Munson is considered by wine historians to be the most influential researcher of viticulture of the 19th century. In short, Munson helped save the French wine industry from a vineyard blight in the 1880s by sending Texas grapevines to fortify the old-world vineyards. I would like to share some passages from “The Grape Man of Texas” by Matt Joyce, which tells Munson’s story.

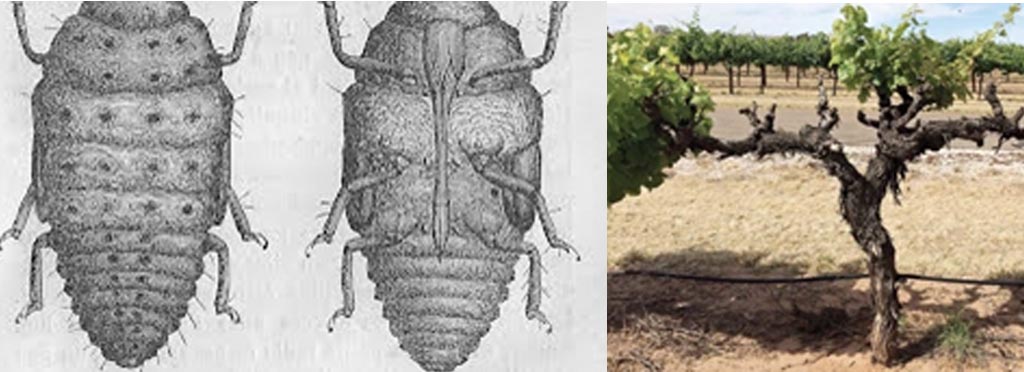

In the mid-19th century, French wine was an international phenomenon and big business, accounting for more than 15% of France’s federal tax revenue. But in 1865, a root louse called phylloxera began wiping out the country’s vineyards. Desperate for a solution, the French reached out to American botanists, including Munson, who was known for his pioneering documentation of native grapevines in Texas and the Southwest. Munson found and sent specific disease-resistant grapevine cuttings to France, where farmers grafted their grapevines to the Texas roots—literally binding the two together—and crossed them with local plants.

Phylloxera was subsequently stopped in its tracks. All those delicate genetic materials of the French grape varieties were rescued from extinction, including Cabernet, Merlot, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Even now, 135 years later, France grows wine grapes rooted on the descendants of Texas native plants.

Born in Illinois in 1843, Munson grew up on a farm and attended college in Kentucky, where he became interested in the idea of improving grapes. As Munson wrote in his 1909 book, Foundations of American Grape Culture, he began his life’s work of experimenting with grape hybrids “So as eventually to supply every use and every season with this most beautiful, most wholesome and nutritious, most certain and profitable fruit.”

Munson opened a commercial nursery after moving to Denison, and each fall he would set out across the country to document every species of wild grape he could find. He scoured Texas, Native American Territory, Mexico, and nearly every state, collecting cuttings and sending them back to Denison by train.

By that time, the phylloxera blight had brought European grape growers to their knees. The pest would eventually destroy two-thirds of the continent’s vineyards, including the majority in France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, and Germany. Remedies such as pesticides and field floods proved ineffective or impractical. Initial efforts to introduce American rootstock had failed because the new varieties withered in French soil. That added to skepticism among the Europeans, who were already wary because, decades earlier, American imports had introduced phylloxera in the first place.

The French turned to the United States, where native grapes evolved to tolerate phylloxera. Munson identified a few species of grapes found in Central Texas, especially the Bell County area around present-day Fort Hood, where the limey soil is similar to that of southern France. Ultimately it was the cuttings from the scrubby limestone hills of Texas that turned the tide of the vineyard blight.

At Grayson College’s West Extension campus, the Munson Memorial Vineyard preserves 65 of the 300 grape varieties Munson developed. (The other 235 have been lost to history.) The vineyard gets about 100 calls a year from grape growers across the country who request cuttings to grow their own Munson vines.

Just up the hill from the vineyard, the college’s Viticulture and Enology Program instructs students in growing grapes (viticulture), making wine (enology), and distilling. Munson photographs and awards adorn the walls, including a replica of the French Legion of Honor medal that was presented to Munson in 1888.

Munson’s work informs the science that goes into planting a vineyard and choosing the best rootstocks for the local conditions. Texas rootstocks were sent over to Europe to help with their grapes, and now we have their grapes growing here in Texas.

Fortunately, Thomas Munson had a very understanding family who were not bent out of shape every time he disappeared into the woods or across the country hunting for more grapes.

His operating freedom and dedication saved us all.

Joyce, Matt. “How the ‘Grape Man of Texas’ Saved the French Wine Industry.” Texas Highways, https://texashighways.com/culture/history/how-the-grape-man-of-texas-saved-the-french-wine-industry/. Accessed 3 January 2021.